- Home

- Lucille Ball

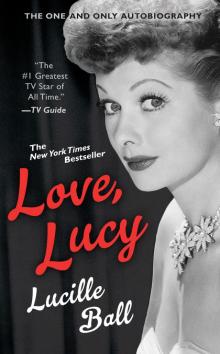

Love, Lucy Page 10

Love, Lucy Read online

Page 10

One reviewer said of Dance, Girl, Dance, “Miss O’Hara, after the usual mishaps, realizes her ambition to become a ballet dancer and Lucille Ball, her rival, becomes the sort of woman other women describe in a single word. Nevertheless, it is Miss Ball who brings an occasional zest into the film, especially that appearance in the burlesque temple where she stripteases.”

We were filming this scene the day I first met Desi, on the RKO lot. I was wearing a slinky gold lamé dress slit up to my thigh, and my long reddish-gold hair fell over my bare shoulders. I also sported a fake black eye, where my lover had supposedly socked me.

George Abbott, who was lunching at the studio commissary with the New York cast of Too Many Girls, called me over. Desi reared back at the sight of me. “Whatta honk of a woman!” he gasped.

At the end of the day’s shooting, I was in slacks and a sweater, my face washed and my long red hair pulled neatly back in a bow. Desi didn’t recognize me as the wild woman he had met at lunch, and had to be introduced all over again. He invited me to dinner and I accepted.

We went to a nightclub, but instead of joining the conga line we sat at a small table, talking and talking. I might as well admit here and now I fell in love with Desi wham, bang! In five minutes. There was only one thing better than looking at Desi, and that was talking to him.

Desi’s real name, he told me, rolling all his r’s magnificently, was Desiderio Alberto Arnaz y de Acha III. He was an only child and born with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth. His family owned cattle ranches and townhouses in Cuba. Desi’s father, a doctor of pharmacology, was mayor of Santiago for ten years; his mother, Delores, was a famous beauty and one of the heirs to the Bacardi rum fortune.

At sixteen, Desi had his own speedboat and motorcar and three different homes. He had never faced a worry or a strain. He loved his life, and everyone loved him.

Then came one of those revolutions that frequently erupted in Cuba. Desi and his mother were alone at one of the family ranches when he awoke to shouts and gunfire. From the window he could see soldiers on horseback slaughtering cattle and setting fire to outbuildings. Desi’s father was in Havana at the time, six hundred miles away at the other end of the island.

Desi’s mother ran through the house collecting all the loose cash she could find and her pet Chihuahua. A cousin arrived just in time to rush them into safe hiding. Desi and his mother, looking back, saw their house in flames.

“Mi casa!” she screamed and screamed until it was out of sight.

Whenever they passed rebel soldiers, to avoid attack (or recognition) Desi would wave and shout, “Viva la revolutión!” He and his mother stayed in hiding in an aunt’s house in Havana for six months. Desi’s father, along with the rest of the Cuban Senate, was locked up in the Morro Castle fortress.

All the family property was confiscated; they lost everything. When he was finally released, Desi’s father decided to go to Florida and start over. Desi would join him soon. Mrs. Arnaz would stay with a sister in Cuba until they had enough money saved to send for her.

Desi was seventeen when he arrived penniless in Miami, with only the clothes on his back. He found his father in a dingy rooming house, heating canned beans on a hot plate. But even this place was more than they could afford, so they moved into an unheated warehouse filled with rats. When Desi saw his father—the former mayor of Santiago, one of Cuba’s biggest cities—chasing rats with a stick, he put his head in his hands and cried.

As he told me the story, Desi’s eyes filled with tears. I began to sniffle too, thinking about my own grandfather and how his life had been ruined through no fault of his own. I knew just how Desi felt.

Though just a kid, and with only a few words of English, Desi hadn’t sat around feeling sorry for himself and waiting for the welfare workers. He went out to look for a job—any job. He earned his first money cleaning out canary cages for a pet store. Next he drove a banana truck.

Desi had been attending the Colegio de Dolores in Santiago, and eventually graduated from St. Patrick’s High School in Miami with A’s in English and American history. He was nominated “most courteous” of his class. Desi’s parents had taught him good manners; driving trucks and taxis after school didn’t change his gentlemanly ways.

In 1936, when Desi was nineteen, he heard that a big-time rumba band at the famous Roney-Plaza in Miami Beach needed a singing guitarist. In a dress suit borrowed for the one-night tryout, Desi got shakily to his feet and sang what was later to become his signature song, the weird and wonderful “Babalu.” He couldn’t have known he’d wind up crooning that song about ten thousand more times. Desi and “Babalu” are sort of like Judy Garland and “Over the Rainbow.”

The applause almost knocked Desi over. Then he looked up and saw dozens of his former classmates from St. Patrick’s High in the audience with their parents. Desi, being Desi, started to cry; the audience clapped harder than ever, and Desi was hired. The pay was no great shakes—fifty dollars a week—but the first thing Desi did was send for his mother. But his father had fallen in love with an American woman who wasn’t about to be relegated to a Latin man’s casa chica, so his parents were divorced shortly thereafter and he gallantly assumed the responsibility of supporting his mother from that day forward.

One night while Desi was at the Plaza, Xavier Cugat caught his act and asked him to audition. Cugat gave him a job as a singer traveling around the country, but he wasn’t paid nearly as much as he knew he was worth. Eventually Desi decided to quit and go back to Miami with his mother and start a band of his own.

He soon learned that in striking out on your own, you have to throw out your chest and sell yourself. The Depression was still hanging on and band jobs were scarce.

One day, Desi found himself down to his last ten dollars. Desi’s a gambler at heart, so with his pockets full of his Cugat press clippings, he strutted into Mother Kelley’s and ordered filet mignon, champagne, cherries Jubilee, and a big two-dollar Havana cigar. When the manager stopped by his table, Desi pulled out his clippings. Cugat was begging him to return, he bragged, but he wanted to start his own band. Before the evening was over, the manager had hired Desi to organize a Latin band for a new nightclub he was opening.

Cugat sent him some musicians—none of whom played Latin music. They were billed as the Siboney Septet, although there were actually only five members. Desi sang and played the guitar. “We sounded so terrible,” he told me on our first date, “that to entertain the publeek, I start them doing la conga. Thees ees a dance we do in Santiago de Cuba at carnival time. You get in a beeg line and hold the heeps of the girl in front of you, and then you one, two, tree, keek! I called it my ‘dance of desperation,’ but it worked and soon there were conga lines all over the country. Even the Rockefellers are doing eet in Rockefeller Plaza.”

In 1938 a New York agent spotted Desi, and next thing he knew, he was the headline attraction in a New York nightclub called La Conga. After he had been there only four months, producer-director George Abbott and Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart offered him a lead part in their Broadway show Too Many Girls. “Ever acted before?” Mr. Abbott wanted to know.

“Me? All my life!” Desi laughed.

The show opened in Boston, and overnight Desi was a sensation. For the seven months the show ran on Broadway, he was the matinee idol of New York. “And here I am in Hollywood,” Desi concluded his life story about three a.m. “Fantasteek, eesn’t eet?”

I wasn’t surprised; I’d heard this same rags-to-riches story in Hollywood a hundred times. For the old star system wasn’t built on talent, or hard work, or acting experience; it was personality that counted. And Desi sure had it.

He enjoyed being the newest male idol but he didn’t really believe it. He used to say that he came to this country with nothing, and he’d go with nothing, but at least he’d leave with an extra pair of shoes.

While he had the money, he loved spending it. He roared around Hollywood in a black foreign-made spor

ts car with his initials in gold; beside him sat a succession of movieland’s most beautiful single girls—usually blondes: Betty Grable, Gene Tierney, Lana Turner. But more and more, he kept turning up on my doorstep at Ogden Drive, where Grandfather would read him editorials from the Daily Worker. Desi was hungry for a family; he’d been rootless for so long.

Everyone at the studio knew I was starry-eyed over Desi, and most of them warned me against him. “He’s a flash in the pan,” I was told, and, “He’s too young for you.” Or, “He’s a dyed-in-the-wool Catholic and you’re Protestant,” and so on.

But I had flipped.

I kept Desi driving up and down the coastline visiting spots I’d seen in my seven years in California, from San Francisco to Tijuana, below the Mexican border. I wanted to share every experience with him, the past included. I even took him to Big Bear Mountain, where we had filmed Having Wonderful Time. I was in slacks, shirt, and bandanna; Desi was in an open-necked shirt, tanned the color of mahogany. We looked like a couple of tourists.

Desi ordered a ham-and-cheese sandwich and a beer at Barney’s, the local bar-café, and then disappeared to wash his hands. The waitress looked at me and then at Desi’s retreating back. “Hey,” she said disapprovingly, glancing from my red curls to Desi’s blue-black hair, “is he Indian? Because we’re not allowed to serve liquor to Indians.”

Nobody could picture us as a couple, not even a tourist-hardened waitress.

Too Many Girls was a fun movie to make. Eddie Bracken and Hal LeRoy had been in the original Broadway production along with Desi; Frances Langford, Ann Miller, and I played a trio of coeds. The best of the Rodgers and Hart tunes in the show, “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was (Till I Met You)” expressed my feelings about Desi exactly.

“He’s another Valentino,” the studio bosses predicted. Even the blasé girl extras went around calling Desi “Latin dynamite.” Because of Desi’s great sex appeal, naturally the RKO bosses wanted to keep him single. His five-year contract, signed before he came to Hollywood, prohibited him from marrying for that length of time.

In September 1940, after the movie was finished, Desi’s six-month option was picked up. His RKO contract allowed him half a year on the road, and the same number of months in Hollywood. The author of Too Many Girls, George Marion, Jr., was busy writing another Broadway musical in which Desi would star, and RKO had two future movies lined up for him. Meanwhile, the original cast of Too Many Girls was opening in Chicago on Labor Day and Desi trained out to join them. I followed in a few days, and we were snapped by the press together at the Pump Room, Desi gazing into a champagne glass and me gazing at him. “She eyes Arnaz,” ran the caption.

“You’ve hit the jackpot at last,” a friend at the table told Desi.

“I doubt eet,” he replied cheerfully, “but anyway, the best thing that happened to me thees year was meeting Lucille.”

Boy, I melted right into his arms. We were criticized for kissing and hugging so much in public, but we were both so gone we didn’t care.

I returned to Hollywood to make a movie, and Desi sent me his first telegram, the first of thousands. It was dated October 15, 1940, from Chicago: “Darling, I just got up. I loved your note and adore you. Loads and loads of kisses, Desi.”

After Too Many Girls closed in Chicago, Desi signed as a headliner with a traveling band. I began making A Girl, a Guy and a Gob, which Harold Lloyd produced for RKO. Eric Pommer had hailed me as a “new find,” so when Mr. Lloyd asked for me for his picture, the studio bosses said okay. It was a rosy, wonderful time for me. I adored the movie; I had a great time making it.

This was the first Harold Lloyd comedy in which he didn’t appear. I played a poor working girl with a screwball family. George Murphy was a sailor and Edmond O’Brien a rich young scion pursuing me. “The lady’s family is a little touched,” wrote the New York Times reviewer. “They play cops and robbers in the parlor, chin themselves in doorways and dance an impromptu conga while Mrs. Leibowitz upstairs gives birth to a son and heir. Lucille Ball may not be made of rubber, but she has as much bounce.”

The Philadelphia Ledger said, “A ribticklish comedy . . . Lucille Ball is more sympathetic than she’s usually allowed to be.” The Dallas Morning Times wrote, “Lucille Ball as the daughter of an engaging screwball family handles her task as a romp.” The New York Post: “Miss Ball has been good for quite some time and now she’s better. Bigger pictures than this are calling her.”

“Lucille Ball is a dazzling comedienne,” another reviewer said. “Beautiful, witty, and with flair. . . . She does a wonderful job of eating an ice cream bar while weeping.”

“Darling, I’m in Knoxville,” Desi wired me from Tennessee, “and we haven’t been able to find a girl to dance with me in the whole town. They haven’t even heard of rumbas. I’m so lonesome and bored and worried about that appearance tomorrow.”

Then he wired, “Darling, things look swell. I miss you so very much and I’m awfully sorry if I was mean the other night but I love you so much I guess I lost my head. Darling, it was wonderful talking to you tonight but awful when I hung up and was left alone. I’m getting a release from the show and hope to be able to see Palm Springs. Whooppee. Love, Desi.”

We saw each other briefly, and then Desi signed for an important appearance at the Versailles nightclub in New York. From there he wired me, “Sweetheart, it is wonderful to know exactly what one wants. These few weeks away from you have been very sad and painful but they have showed me that I want you and you always.”

A few days later he wired again from New York: “I’m so glad you called, Darling. Even if things look bad to you from so far away, please don’t make too quick conclusions. I really miss you immensely and am so anxious for you to come to town. So please trust me a little bit, will you? I love you very much.”

I knew that Desi had all the debutantes afire again, and pursuing him like crazy. Finally, RKO decided to send me and Maureen O’Hara east to publicize our new movie, Dance, Girl, Dance. It bugged me that everywhere we went, Maureen was treated like a lady and I got a stripteaser’s reception. An actress gets typed and her real personality is lost in the shuffle.

In Buffalo, my old sidekick from Jamestown High School days, Marion Strong, came to see me and I bubbled and raved about Desi. She had seen me through other love affairs but I had never been so sold on any man before.

Thanksgiving I spent with Desi in New York. We’d been separated for a whole month; again, we couldn’t stop talking.

The movie we had made together, Too Many Girls, opened at Loew’s Criterion and got fine reviews, although Desi’s were somewhat mixed. Howard Barnes wrote, “Desi Arnaz is fine as the South American football wonder,” but Bosley Crowther wrote rather sourly in the New York Times, “Mr. Arnaz is a noisy, black-haired Latin whose face, unfortunately, lacks expression and whose performance is devoid of grace.”

Since Desi was packing them in five shows a day at the Roxy and his appearances at the Versailles were a sellout, he could afford to ignore Mr. Crowther. We had other fish to fry. All we could think and talk about was our future.

One night we sat at a small table at El Morocco and hashed and rehashed our problems. A photographer snapped our picture, and it shows us both staring at the table looking deeply sad and troubled. We discussed the six-year difference in our ages (this bothered only me) and Desi’s Catholicism.

Our outlooks on life were very different. Desi’s family ranches stretched as far as he could ride a horse in a day. I was raised in a little white house near the railroad tracks and an amusement park; I never even owned a bicycle as a kid. When Desi was fifteen, he was living like a young prince, with cars and speedboats and horses; I was looking for a penny to make subway fare in New York. Desi was raised with the idea that the man’s word is law; he makes all the decisions; God made woman only to bear children and run the home.

I wanted a masterful husband, God knows—and part of me wanted to be cherished and cared for. B

ut all my life I’d been taught to be strong and self-reliant and independent, and I wondered if I could change.

We weren’t competitive in our careers. Desi’s name was as well known in show business as mine and he made just as much money. But he was supposed to spend six months of the year in Hollywood and six months on the road, and what kind of a life was that for us?

Friends kept pointing out that Desi was a romantic. He lived to enjoy life and never thought of tomorrow. I was a levelheaded realist who never lived beyond my means or went overboard drinking or gambling. Nevertheless, I was emotional and sentimental and romantic, too. I was an actress, wasn’t I?

I can’t do a funny scene unless I believe it. But I can believe wholeheartedly almost any zany scene my writers dream up. No cool-headed realist can do this.

We were both head over heels in love and we both longed with all our hearts for a home of our own and children. But everything else in the picture seemed hopelessly negative; we agreed that night that we could never marry.

The next evening I had to leave New York for a series of personal appearances in the Midwest. In the middle of the night, as the train swayed and rumbled through the hills and valleys of upstate New York, the porter brought me a telegram. It was from Desi. “Just wanted to say I love you, goodnight and be good. I think I’ll say I love you again, in fact I will say it. I love you love you love you love you.” That was one prop I didn’t handle so well. My tears practically turned the telegram to pulp.

I thought everything was over, but Desi couldn’t say good-bye. He phoned me almost every hour in Chicago. Then I took a train to Milwaukee, more depressed than I’ve ever been in my whole life. I had trunkloads of furs and glittering ball gowns with me; I bowed from stages and shook hands and smiled and smiled and smiled. No one guessed my real feelings.

Love, Lucy

Love, Lucy