- Home

- Lucille Ball

Love, Lucy Page 16

Love, Lucy Read online

Page 16

When the deal was finally set, it was late March. We had to start filming by August 15 to be on the air by October. We could rehearse and film a half-hour show in a week, but cutting, editing, and scoring would take another five weeks at least.

We began discussing possible writers. First comes the script, and then the interpretation and improvisations. Both of us admired and liked my three radio writers, Madelyn Pugh, Bob Carroll, Jr., and Jess Oppenheimer. As Jess says, “In a show that’s destined to be a hit, nothing but happy things happen. God’s arm was around us.”

As Lucy Ricardo, I played a character very much like Liz Cugat on my radio show. Lucy was impulsive, inquisitive, and completely feminine. She was never acid or vicious. Even with pie on her face she remained an attractive and desirable female, stirred by real emotions.

Lucy Ricardo’s nutty predicaments arose from an earnest desire to please. And there was something touching about her stage ambitions. As we were discussing her with our writers, Desi spoke up. “She tries so hard . . . she can’t dance and she can’t sing . . . she’s earnest and pathetic. . . . Oh, I love that Lucy!” And so the title of the show was born.

Desi was cast as the steadying, levelheaded member of the family, a practical man and a good money manager. He tolerated his wife’s foibles good-naturedly, but he could only be pushed so far. The audience had to believe that I lived in fear and trembling of my husband’s wrath, and with Desi, they could. There was also a chemistry, a strong mutual attraction between us, which always came through.

At the very first story conference, Desi laid down the underlying principles of the show. The humor could never be mean or unkind. Neither Ricky nor Lucy would ever flirt seriously with anyone else. Mothers-in-law would not be held up to ridicule. Most of all, Desi insisted on Ricky’s manhood. He refused to ever be a nincompoop husband. “When Lucy’s got something up her sleeve that would make Ricky look like a fool, let the audience know that I’m in on the secret,” he told our writers.

I had always known that Desi was a great showman, but many were surprised to learn he was a genius with keen instincts for comedy and plot. He has a quick, brilliant mind; he can instantly find the flaw in any story line; and he has inherent good taste and an intuitive knowledge of what will and will not play. He is a great producer, a great director. He never stays on too long or allows anybody else to.

When we had the characters of Lucy and Ricky clear in our minds, Jess Oppenheimer suggested that we add another man and wife—an older couple in a lower income bracket. The writers could then pit couple against couple, and the men against the women. I had known Bill Frawley since my RKO starlet days as a great natural comic; we all agreed upon him for Fred Mertz. We then started thinking about a TV wife for Bill.

We considered a number of actresses, and then one day Desi heard about a fine actress from the Broadway stage named Vivian Vance. She was appearing that summer in The Voice of the Turtle at La Jolla Playhouse. The ride down the coast was too much for my advanced state of pregnancy, so Jess and Desi drove down without me. They liked how Vivian handled herself on the stage and the way she could flip a comedy line. So they hired her on the spot.

As far as I was concerned, it was Kismet. Viv and I were extraordinarily compatible. We both believe wholeheartedly in what we call “an enchanted sense of play,” and use it liberally in our show. It’s a happy frame of mind, the light touch, skipping into things instead of plodding. It’s looking at things from a child’s point of view and believing. The only way I can play a funny scene is to believe it. Then I can convincingly eat like a dog under a table, freeze to death beneath burning-hot klieg lights, or bake a loaf of bread ten feet long.

We had no way of knowing how comical she and Bill would be together. Vivian was actually much younger than Bill. Up until then, she’d usually been cast in glamorous “other woman” parts. But she went along gamely with Ethel Mertz’s dowdy clothes, no false eyelashes or eye makeup, and hair that looked as if she had washed and set it herself. But she drew the line at padding her body to look fatter.

Time and again she told Jess Oppenheimer, “If my husband in this series makes fun of my weight and I’m actually fat, then the audience won’t laugh . . . they’ll feel sorry for me. But if he calls me a fat old bag and I’m not too heavy, then it will seem funny.”

Vivian was unhappy in her marriage to actor Philip Ober and so she ate; after a while Jess stopped insisting that she pad herself. On summer vacations she’d diet, and once she came back on the set positively svelte. “Well, Vivian,” I kidded her, “you’ve got just two weeks to get fat and sloppy again.”

She and Bill scrapped a good deal, and this put a certain amount of real feeling into their stage quarrels. Bill became the hero of all henpecked husbands. He couldn’t walk down the street without some man coming up to him and saying, “Boy, Fred, you tell that Ethel off something beautiful!”

So much good luck was involved in the casting. Early in the series, our writers wanted to write a show in which the Mertzes had to sing and dance. We then learned for the first time that both Vivian and Bill had had big musical comedy careers. Vivian had been in Skylark with Gertrude Lawrence, and Bill was a well-known vaudeville hoofer.

I had insisted upon having a studio audience; otherwise, I knew, we’d never hit the right tempo. We did the show every Thursday night in front of four hundred people, a cross-section of America. I could visualize our living and working together on the set like a stock company, then filming it like a movie, and at the same time staging it like a Broadway play. “We’ll have opening night every week,” I chortled.

Desi’s first problem was that there were no movie studios in Hollywood with accommodations for an audience. We also wanted a stage large enough to film the show in its natural sequence, with no long delays setting up stage decorations or shifting lights.

Desi hired Academy Award-winning cameraman Karl Freund, whose work I had admired at MGM, and discussed the problems with him. Karl flew to New York for a week to see how television cameras could be moved around without interfering too much with the audience’s view of the action. He came back pretty unimpressed. “There are no rules for our kind of show, so we’ll make up our own.”

Karl Freund hit upon a revolutionary new way of filming a show with three cameras shooting the action simultaneously. One of these cameras is far back, another recording the medium shots, with a third getting the close-ups. The film editor then has three different shots of a particular bit of action. By shifting back and forth between the three, he can get more variety and flexibility than with the one-camera technique.

But moving three huge cameras about the stage between the actors and the audience called for the most complex planning.

First Desi rented an unused movie studio. By tearing down partitions, he joined two giant soundstages. This gave us enough room to build three permanent sets—the Ricardo living room, bedroom, and kitchen—and a fourth set, which was sometimes the New York nightclub where Ricky worked and sometimes an alligator farm or a vineyard in Italy or the French Alps—whatever the script called for. We even turned that thirty-foot set into the deck of the USS Constitution once.

The roving cameras couldn’t roll easily on the wooden stage, so a smooth concrete floor was laid down. Each week a complicated pattern of chalk instructions was drawn on the cement, indicating each camera’s position for every shot. This is known as camera blocking, and took two full days.

Desi and I okayed each pillow, picture, pot, and pan that went into the Ricardos’ apartment, to make sure it was authentically middle-income. While the three rooms slowly took form before our eyes, bleachers for three hundred people were built facing them. The Los Angeles Fire and Health departments threw a mountain of red tape at us when they learned we were inviting a large weekly audience into a movie studio. Desi had to add rest rooms, water fountains, and an expensive sprinkler system. Microphones were installed over the heads of the audience; we wanted our laughs live—so

me of the canned laughter you hear today came from our Lucy show audiences.

Desi and I were so excited and happy, planning our first big venture together. I thought that I Love Lucy was a pleasant little situation comedy that might even survive its first season. But my main thoughts centered on the baby. The nursery wing was now complete and I planned to have a natural delivery late in June. And so I happily waited, and waited, thirty pounds heavier than ever before. I was so proud of that big stomach of mine. Desi, knowing that my grandmother Flora Belle had been one of five sets of twins, expected triplets.

The weeks passed and still no baby. Finally my obstetrician decided on a cesarean delivery. Lucie Desirée Arnaz was lying sideways with her head just under my rib cage; when they performed the cesarean, the surgical knife missed her face by a hairsbreadth. But miss her it did; she was complete, healthy, and beautiful. She arrived at eight-fifteen a.m. on July 17, 1951, weighing seven pounds, eight ounces. Lyricist Eddie Maxwell wrote the words to a song in her honor, “There’s a Brand-New Baby at Our House,” and Desi sat up all night with his guitar composing the music. The next day, the proud papa passed out Havana cigars to his entire studio audience and introduced his new daughter and that song to the world on his new CBS radio show, Tropical Trip. Later on, it was used on the show when Lucy Ricardo had her baby.

The day that Lucie and I were to leave the hospital, Desi appeared in a long, dark blue sedan, our new “family” car. He drove us home at a sedate crawl and the baby and her nurse were installed in their private wing.

Lucie’s coming changed our life completely. Before, there had been two professional people in the house, discussing deals and contracts and money matters and scripts. Now suddenly there was a fragile little new spark of life there, affecting everything we thought or did.

God . . . how I love babies! Not just my own, but the world’s babies . . . I’m so sorry that I can’t have any more. I had to go right back to work after Lucie was born, so I missed hours and hours and hours of her earliest life. When Lucie stopped sleeping most of the day, it got especially tough to leave her for the studio. Once there, I was seldom home again before midnight. During the early days of the I Love Lucy show, I only had Sundays free. So I spent this time entirely with my new baby, marveling at her.

It took me a long time to recover physically from Lucie’s birth, but I had no time to pamper myself. Six weeks after she arrived, I walked on the Lucy set to start filming the series.

Rehearsals got under way to the pounding of hammers and buzzing of saws; the set was only half built and a whole wall of the soundstage was still missing when we started. Desi was so nervous that he memorized everybody’s lines and moved his own lips as they spoke; he also kept flicking his eyes around the stage watching the progress of the three cameras. He soon got over this, but proved to be the fastest learner of dialogue.

To my delight, I discovered that the I Love Lucy show drew from everything I’d learned in the movies, radio, the theater, and vaudeville. I wanted everything about the venture to be top-flight: the timing, the handling of props, the dialogue. We argued a good deal at first because we all cared so passionately; sometimes we’d discuss phrasing or word emphasis in a line of dialogue until past midnight. Bill Frawley couldn’t understand the need for all this hairsplitting. He’d tear his part out of the script, memorize it, and pay no attention to what the rest of us were saying or doing. Vivian, like me, was a perfectionist who took her profession very seriously. “Now what’s my motivation here?” she’d ask me or Desi or Jess, and this would launch a half-hour discussion. Bill couldn’t have cared less. If he got his big laugh, he didn’t care how or why. And actually, Bill can be funny doing nothing. He has that kind of face, and in any kind of costume he’s hilarious.

During one early rehearsal, Vivian was championing a particular way in which a line should be spoken. Nobody agreed with her, but she kept explaining and explaining, until finally we did see the logic of her position. By this time it was two a.m. and she was so wound up she couldn’t stop talking. She went on and on until Desi tapped her gently on the shoulder. “Vivian, your yo-yo string is tangled.”

I could sense a flaw in the story line or dialogue but I couldn’t always put my objections into words. Frustrated, Desi would burst into a flood of Spanish. I’d express my frustrations by getting mad. Vivian was a tower of strength in such circumstances; she would intuitively guess what was wrong and then analyze it. She would make a great director.

We rehearsed the first show twelve hours a day. Then on Friday evening, August 15, 1951, the bleachers filled up by eight o’clock and Desi explained to the audience that they would be seeing a brand-new kind of television show. He stepped behind the curtain and we all took our places.

Sitting in the bleachers that first night were a lot of anxious rooters: DeDe and Desi’s mother, Dolores; our writers; Andrew Hickox; and a raft of Philip Morris representatives and CBS officials. To launch the series, the network had paid out $300,000. They hoped it would last long enough to pay back that advance.

We were lucky all the way. The first four shows put us among the top ten on television. Arthur Godfrey, one of the giants, preceded us and urged his watchers to stay tuned to I Love Lucy. Our twentieth show made us number one on the air and there we stayed for three wild, incredible years.

I Love Lucy has been called the most popular television show of all time. Such national devotion to one show can never happen again; there are too many shows, on many more channels, now. But in 1951–1952, our show changed the Monday-night habits of America. Between nine and nine-thirty, taxis disappeared from the streets of New York. Marshall Fields department store in Chicago hung up a sign: “We Love Lucy too, so from now on we will be open Thursday nights instead of Monday.” Telephone calls across the nation dropped sharply during that half hour, as well as the water flush rate, as whole families sat glued to their seats.

That season Red Skelton got the Emmy Award in February 1952, but told the nation, “You gave this to the wrong redhead. I don’t deserve this. It should go to Lucille Ball.” During our first season someone told Desi that our show had a hit rating of 70. He looked worried, thinking that a “grade” of 70 was barely passing. “You’re kidding,” he said, not realizing that a rating of 70 was indeed phenomenal.

* * *

In May 1952, Desi and I both walked into Jess Oppenheimer’s office, elated.

“Well, amigo,” Desi told Jess, “we’ve just heard from the doctor. Lucy’s having another baby in January. So we’ll have to cancel everything. That’s the end of the show.”

My feelings were mixed. I felt bad for the cast, the crew, and the writers. I regretted that our dream of working together was again busted. But my predominant feeling was still one of elation. Another baby! And I was almost forty-one!

Jess sat looking at us silently. Then he remarked casually, “I wouldn’t suggest this to any other actress in the world—but why don’t we continue the show and have a baby on TV?”

Desi’s face lit up. “Do you think we could? Would it be in good taste?” No actress had ever appeared in a stage or television play before when she was obviously pregnant.

“We’ll call the CBS censor and see,” said Jess. That wonderful guy said, “I don’t see why not,” and with his active encouragement, Philip Morris and the network went along with it. We had just finished forty Lucy shows, ten months of backbreaking work with hardly a letup, but now we made feverish plans to get into production for the next season as fast as possible.

The baby would be delivered by cesarean section, so we had a definite date to plan around: January 19. We took only a two-week vacation that summer, beginning the new shows in June. All through the hot, steaming Hollywood summer we worked, ten and twelve hours a day, six days a week. In the early fall, when I was beginning to look pretty big, we did seven shows concerning my pregnancy. These films were screened by a priest, a minister, and a rabbi for any possible violation of good taste. It was the

CBS network that objected to using the word “pregnant.” They made us say “expecting.” The three-man religious committee protested, “What’s wrong with ‘pregnant’?” They were heartily in favor of what we were doing: showing motherhood as a happy, wholesome, normal family event.

Many times on the Lucy show the script was very close to reality. In real life Desi and I had separated and reconciled many times, and the public knew this. So our writers did a script about Lucy and Ricky quarreling and separating. Ricky Ricardo moved out of the apartment and I was supposed to walk around the living room set, forlorn, touching each piece of furniture wistfully.

To our writers’ amazement, people in the studio audience took out their handkerchiefs and started weeping. Then when Ricky and Lucy were reconciled a few minutes later, in what was supposed to be a hilarious scene, nobody laughed. They were too happy and relieved to see us together again.

Because the audience knew that Desi and I were really married, they assumed that Vivian Vance and Bill Frawley were, too. When Desi would announce, “And here’s Vivian’s real husband, Philip Ober!” they would sit in stunned disbelief. Even Vivian’s father was caught up in the make-believe. “Why don’t you use your own name on the show?” he asked Vivian. “Fred Mertz does.”

Both times I was pregnant, I mooned for hours over a baby photograph of Desi, hoping by some magic I would have a baby who looked just like him. Then we did a show where Lucy tells Ricky she is having a baby. She sends an anonymous note to him at his nightclub, requesting that he sing “Rock-a-Bye Baby.” Ricky complies, going from table to table singing the old nursery rhyme. In front of Lucy’s table, he looks into her eyes and suddenly realizes that he is the father. When we did this scene before an audience, Desi was suddenly struck by all the emotion he’d felt when we discovered, after ten childless years of marriage, that we were finally going to have Lucie. His eyes filled up and he couldn’t finish the song; I started to cry, too. Vivian started to sniffle; even the hardened stagehands wiped their eyes with the backs of their hands. The director wanted retakes at the end of the show, but the audience stood up and shouted, “No, no!”

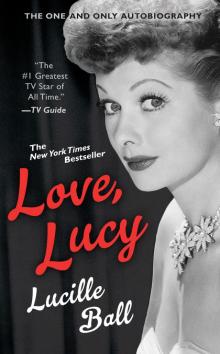

Love, Lucy

Love, Lucy