- Home

- Lucille Ball

Love, Lucy Page 4

Love, Lucy Read online

Page 4

It takes me a long time to get angry, but when I do it’s such a compilation of things over a long period that nobody can quite understand what triggered it finally . . . even myself.

There’s a great deal of difference between temperament and temper. Temperament is something you welcome creatively, for it is based on sensitivity, empathy, awareness . . . but a bad temper takes too much out of you and doesn’t really accomplish anything.

When I got to be thirteen, a lot of pressures that had been building up for years suddenly found expression. Most of my stunts were the kind of silly antics most teenagers do to draw attention to themselves. On a dare, I roller-skated on the freshly varnished school gymnasium floor . . . tore through Celoron sitting on the front radiator of a boy’s tin lizzie . . . And I ran away a lot. I’d leave the classroom for a drink of water and never come back.

Looking back, I think my main need was for somebody to talk to, to confide in, some wise and sympathetic older person. My school principal, Bernard Drake, became such a person. Mr. Drake was the first person to label my exuberant feelings as talent and to urge me to go on the stage. In the eighth grade, I had many long, satisfying talks with him. Then he left Celoron to work at a state normal school. I missed him so much that one day I took little Cleo by the hand and we hitchhiked fifty miles to his new home. He called DeDe and had us on a bus the next morning.

The summer that I was fourteen an immense restlessness swept over me. Things weren’t going too well at home. DeDe and Ed got divorced five or six years later, but the first real fights and arguments started at about this time. My mother’s face grew pinched with worry and often a taxi would bring her home from the store in the middle of the afternoon, suffering one of her migraine headaches. She would lie in a darkened room with the shades down, unable to move or talk, until the attack passed. I worried about her and the hard life she led.

Grandpa Hunt wasn’t too happy either, running his lathe at Crescent Tool. Ever since Grandmother Flora Belle died, he seemed torn loose from his moorings. It made him mad that the factory workers shared little of the great prosperity then sweeping the country. This, of course, was long before the days of Social Security or unemployment benefits; when a man lost his job, his family could starve, and a serious illness could bankrupt him for life.

All the local kids got summer jobs at the amusement park; I was hired as a short-order cook at a hamburger stand. I took my job seriously and loved earning the money. “Look out! Look out! Don’t step there!” I’d suddenly holler at some person passing by, and as he stopped, startled, one foot in midair and looking worriedly at the ground, I’d continue: “Step over here and get yourself a de-licious hamburger!” This mesmerized a lot of people into buying, and incidentally, they were darn good hamburgers.

DeDe kept a strict check on me, and I had to be home at a certain time each night. I wasn’t allowed to go out in any canoes. The one time I decided to live dangerously and went canoeing with a boy, I had to tip it over to get back. I got wet but was still virtuous!

DeDe had to force me to go to my first dance at the Celoron Pier Ballroom. They still had all the big-name bands, like Harry James and Glenn Miller and Benny Goodman. DeDe let me wear lipstick, and she made me a perfectly beautiful dress of pussy willow taffeta with a band of real fur around the bottom. A girl at the dance wearing some stale dress oohed and aahed over it and then asked, “Can I have it?” The next day I gave it to her. DeDe was furious, and I don’t blame her. But this girl came from a very large, poor family and never had any nice things.

But the most momentous thing that happened to me during my fourteenth summer was that I fell in love. I never laugh at puppy love, or shrug it off; my kids are going through their first wild crushes, and I know how they can hurt. Anyway, DeDe was away most of the time at the store, Ed paid little attention to us, and Daddy spent most of his spare time with Freddy. Maybe I was still searching for a father; maybe Johnny reminded me of another Mediterranean type I had once been crazy about, my uncle George. Whatever the reason, the summer I was almost fifteen, I fell deeply in love with an Italian boy of twenty-three.

Johnny Davita had a John Garfield build, but his features were finely chiseled and his dark eyes warm and full of life. He came from a large, prosperous Jamestown family and was studying to be a doctor when I first met him.

At first my nutty antics made him laugh. Then we danced together at the ballroom. He was very sweet and protective toward me. Mainly we talked. I wanted to share with him everything that had ever happened to me, and all my hopes for the future. I had no thought of being an actress then; I just wanted to be somebody, and to make things easier for DeDe.

When my friend Pauline Lopus and I went back to the little red schoolhouse in Celoron in the fall of 1926 as high school freshmen, we were the only girls in the school with boyish bobs. This inspired us to put on our first amateur production, Charley’s Aunt. I had a wonderful teacher that year, Miss Lillian Appleby, who, like Mr. Drake, tried to channel my driving urge to express myself into acting.

DeDe never tried to hem me in. Be an actress? Sure, why not? She sat up until midnight many nights sewing her eyes out, making us costumes, and was in charge of many school productions.

DeDe didn’t turn a hair when we hauled to the school stage all the brown wicker living room furniture she was still buying on time. When my stepfather got home from work, he raised Cain. “There’s no place to sit!” he protested. DeDe shrugged. “We’ll sit on the front porch in the swing till the play is over,” she told him.

For the most part, Ed encouraged my acting. But I don’t think a stage career ever occurred to me until one night when he took me to see the great monologuist Julius Tannen in the Celoron school auditorium. This virtuoso sat in a chair on a bare stage with a single light over his head and transported us wondrously. (Recently, I had a chance to meet Mr. Tannen and tell him what an important part he played in my getting into the business.)

With Charley’s Aunt, I knew for the first time that wonderful feeling that comes from getting real laughs on a stage. I not only played the male lead, but sold the tickets, swept up the stage afterward, and turned out the lights.

The night of the first performance, Pauline stood at the entrance to the school auditorium collecting the tickets. She barely had time to dash backstage and throw on her long Victorian skirts and her bonnet before I yanked the curtain up. She started to speak her opening lines, then stopped, and a funny expression came over her face.

“What’s the matter?” I hissed. “Forget your lines?”

“No,” said Pauline with great annoyance. “I forgot my makeup!”

This was the main reason she wanted to be in the play: the chance to use real makeup with her mother’s approval.

Charley’s Aunt was a great success. We charged twenty-five cents a ticket, and made twenty-five dollars, and gave all of it to the ninth grade for a class party. Pauline and I often recall the thrill that gave us. She still lives in the same little house in Celoron and is now a dedicated guidance counselor, who never stops learning and giving.

The success of Charley’s Aunt encouraged me to get into as many musical and dramatic offerings as I could, from the school drama club to the Shriners’ annual productions. I even bounced up on the stage of the Palace Theater in Jamestown to be photographed by some traveling shyster who had fallen heir to an old camera and some bad film. That was my first moving picture—something called Tillie the Toiler.

When I was fifteen, the Harry F. Miller Company put on a musical called The Scottish Rite Revue on that same Palace stage. I did an Apache dance with such fervor that I fell into the orchestra pit and pulled an arm out of its socket. The Jamestown Post-Journal hailed me as “a new discovery,” and the head of the Jamestown Players, Bill Bemus, told me I was “chock-full of talent.”

That summer I worked at the park at an ice cream stand and danced through the starry summer nights with Johnny. DeDe disapproved of my romance with him. She

felt he was too old for me, and she was troubled by rumors surrounding Johnny’s father and the mob. This was the lawless twenties, the era of the Untouchables, Al Capone, and Prohibition. Technically, everyone who touched alcohol was a lawbreaker: the guy who ran the booze in from Canada and the guy who bought it from him illegally. I thought Prohibition was a silly and impractical law, and so did most people at the time, even DeDe. But my mother didn’t want me involved with anyone who might be deemed unsavory.

Prohibition had a bad effect on Celoron, for with the closing of all public bars, the great resort hotels ringing the lake began to die on their feet. Some were boarded up, others torn down. When the fine restaurants and hotels disappeared, the wealthy oil families from Pittsburgh began to go elsewhere and their big houses stood empty. Beautiful Celoron Amusement Park began to go slightly downhill. It was never a Coney Island—there were no barkers or cheap sideshows—but gradually, the type of people strolling through the park and doing business there changed.

I was much too busy working to pay much attention. I had a few brushes with disaster. I had to run like hell to get out of the way of somebody rolling out of a speakeasy, but just once or twice.

Early one morning, Johnny wasn’t as lucky: His father was shot and killed in front of the Catholic church as he came out of six-o’clock mass. Johnny’s ambition to be a doctor died with his father. From then on, he was head of his family, with a mother and many siblings to support.

DeDe asked Johnny to stay away from me. It didn’t do much good, although, in my heart, I must have known she was right. Eventually, given her opposition and Johnny’s new responsibilities, he and I saw less and less of each other. But our love was the real thing: it remained a love that haunted me for many years—at least until I came to Hollywood.

* * *

The summer following my sophomore year at high school, they held a Miss Celoron bathing beauty contest at the park. Miss America of 1927 was to be the judge, and it was quite a big deal locally.

I didn’t particularly want to be in a bathing beauty contest. I was very skinny, being my present height of five feet seven and a half but weighing less than a hundred pounds. And I had freckles on my back, which embarrassed me terribly. But somebody entered my name, so I went along with it. The feminine ideal at this time was Clara Bow with her heart-shaped face and short ringlets. I tried my darnedest to look like Clara Bow—but to no avail. The candidates were supposed to have their pictures in the paper before the contest, and DeDe sent me to the best photographer in Jamestown, T. Henry Black. It was Mr. Black who was quoted as saying, “It’s very difficult to get a satisfactory picture of Miss Ball because the lady is just not photogenic!”

I think I was runner-up in the contest, but what I remember most is my embarrassment. Only recently have I begun wearing bathing suits again.

Right after the beauty contest came the Fourth of July, the real start of my sixteenth summer and the biggest weekend at the amusement park. My grandfather Fred, in a holiday mood, came home from work on the trolley with a mysterious object wrapped in brown paper. It was a birthday present for Freddy, who was about to turn twelve—a real .22-caliber rifle. Freddy wanted to shoot crows right away, but Daddy told him, “You can’t use it until tomorrow, Fritzie-boy. Tomorrow I’ll show you how.”

Early the next morning the crowds began piling off the trolley and heading toward the lake, with picnic baskets, and the small fry waving little red-white-and-blue flags. It was a bright sunny July day, and the heavy scent of clover floated from the meadow which stretched between us and the railroad tracks. I was in a hurry to get to my hamburger job at the park, but I hung around for a while to watch the gun lesson. Although Cleo and Freddy were big kids now, I still thought of them as my charges.

Daddy set up a tin-can target in our backyard and then in his usual meticulous, careful way explained all about the gun. Besides me and Freddy, there were Cleo and Johanna, a girl Freddy’s age who was visiting someone in the neighborhood. Daddy placed the tin can about forty feet away, in the direction of some open fields where there were no houses.

There was an eight-year-old boy who lived at the corner whose name was Warner Erickson. Every once in a while you would hear his mother shriek, “War-ner! Get home!” and Warner would streak for his yard since his mother spanked him for the slightest infraction. This Fourth of July weekend he had wandered into our yard and was peeking around the corner of our house watching the target practice. We didn’t notice him at first, but then Daddy told him, “Now Warner, please sit down and stay out of the way.” Warner moved close to us and obediently sat down on the grass to watch. My friend Pauline was also watching from a safe distance, on her back stoop.

My brother was shooting at the target, and then it was his little girlfriend’s turn. Johanna picked up the gun and held it against her shoulder with one eye closed. At that moment, we heard a strident, “War-ner, get home this minute!”

Warner darted in the direction of his home, right in front of the rifle. The gun went off and Warner fell spread-eagled to the ground, into the lilac bushes.

“I’m shot! I’m shot!” Warner screamed.

“No you’re not,” said Daddy. “Get up.”

Then we saw the spreading red stain on Warner’s shirt, right in the middle of his back.

Cleo screamed, and I took her in my arms. Warner was exactly her age and was her special playmate. The slam of a screen door told me that Pauline was running to tell her mother. Daddy looked stunned; then he picked up Warner as gently as a leaf. He talked to him in a low, comforting voice. The girl who had fired the gun was in shock.

The balloon ascension was beginning at the park. You could see it drifting up above the trees to the burst of applause below. Warner was quiet in Daddy’s arms as we all walked the hundred yards to his house.

Then Warner’s mother burst out of her back door. At the sight of the blood and her son’s slack body, she began screaming hysterically. There was a long, long wait for the ambulance. While we huddled together in a frightened group, Mrs. Erickson raced up and down the street telling everyone, “They’ve shot my son! They’ve shot my son!”

The next few days were a kind of nightmare as we all hung on to bulletins from the hospital. Then we learned the awful news: a .22-caliber bullet is very small, but by fantastic bad luck, the bullet passed right through Warner’s spine, severing the cord.

One of my first scrapbooks contains a yellowed clipping from the Post-Journal of July 5, 1927: “Warner Erickson, eight years old, of Celoron, is still in critical condition at Jamestown General Hospital as a result of being shot in the back Sunday, July 3, at Celoron. Lucille and Fred Ball were shooting at a target at the rear of their home. The Erickson lad stepped out in the range as Johanna Ottinger, a young girl, fired at about the same time, the bullet entering the boy’s back and passing through his lungs, lodging in the chest. Mr. Hunt, grandfather of the Ball children, was watching the target practice.”

In a week or so, Warner came home from the hospital. His mother often wheeled him up and down the sidewalk in front of our house. Each time Cleo saw him, she started to cry. We were all terribly fond of Warner.

Daddy would have gladly paid Warner’s doctors’ bills the rest of his life, but the Ericksons didn’t come to see Daddy; they went to a lawyer. They planned to sue Daddy for everything he had, they told the whole neighborhood. Feelings ran hot and high, pro and con. Daddy couldn’t believe anyone could even think it was anything but an accident. The possibility of a lawsuit worried him greatly. He was then sixty-two and near the end of his working career. His tiny life savings and the house were all he had to face the future. So on the advice of a lawyer he deeded the house over to his daughters, DeDe and Lola, for payment of one dollar.

It was almost a year before the case came to trial in the county civil court. Daddy was charged with negligence since he had been the only adult present. It was a muggy, overcast day in May 1928, the lilacs in full heady bloom, when Daddy

’s lawyer drove us to the imposing yellow courthouse in Mayville, at the northern end of the lake. The Colonial-style courtroom was large and imposing, with light wood paneling and impressive oil portraits around the room, of judges in their somber robes.

The Ericksons wheeled in young Warner and parked him right in front of the jury box so that everybody could get a good look at him. Two Jamestown doctors who had attended him testified how the bullet had entered his spine. Warner was paralyzed from the waist down for life, they said. He sat listening with bright, intelligent eyes. I was trembling and feeling sick to my stomach; Daddy was white as a sheet.

My grandfather didn’t have many witnesses in his defense: just DeDe, Freddy, Cleo, and me. The visiting girl who fired the shot, Johanna Ottinger, wasn’t there. Her testimony might have helped Daddy a great deal but she was home in another state. In fact, none of us ever saw her again.

Cleo cried on the witness stand, and Freddy and I, scared half to death, stuttered and stammered as we stated and restated all the precautions Daddy had taken; how Warner, uninvited, had been told to sit on the grass at a safe distance and not to move; and how he had suddenly popped up at the sound of his mother’s voice and darted in front of the gun.

The trial began one afternoon and continued into the next morning. Someone got on the witness stand and said that Daddy had made a target out of Warner and let us practice on him. We couldn’t believe our ears. How could anyone possibly blame Daddy for the accident? It was just an inexplicable tragedy.

The jury went out about eleven o’clock in the morning and was gone for four and a half hours. We paced up and down the courthouse corridors for what seemed an eternity. Then the jury solemnly filed back and we learned that the Ericksons had won their case. Daddy had been negligent, they said, and he must pay the Ericksons $4,000, although all the gold in the world couldn’t restore Warner’s ability to walk.

Now, this doesn’t seem like a great deal of money today, but in 1928 it was everything we had. Daddy claimed the house wasn’t his, it belonged to his daughters, but he handed over all his savings and insurance, every cent he had accumulated in a lifetime of hard work, and declared bankruptcy. The Ericksons were not satisfied.

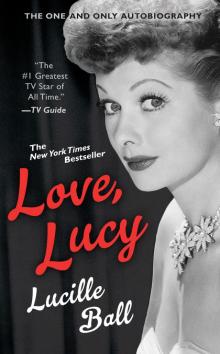

Love, Lucy

Love, Lucy