- Home

- Lucille Ball

Love, Lucy Page 8

Love, Lucy Read online

Page 8

Just watching Lela handle Ginger on the set was an education in itself. Lela would go upstairs and say to the bosses, “You know, it would be a lot easier for Ginger if she had a little bit larger dressing room so she could wash her hair there instead of doing it at home. Ginger hasn’t asked for this, but we could save forty-five minutes every morning if you’d just knock out a wall and give her a little more room.”

Ginger was working so hard that she needed a few assists. She was a sunny, cheerful person, friendly and approachable as a puppy. She never had an entourage to impress other people, as many stars did and still do. She needed a hairdresser right at hand and a choreographer, and a secretary and a press man or two, and when she moved about the lot, they moved too, to save her time. When she walked from her dressing room to the set, seven or eight people came along. Ginger made seventy-one A movies in a period of fourteen years, including nine with Fred at RKO. When one of their films was finally in the can, Fred would sail to Europe to recuperate for six months; Ginger would start a new movie within twenty-four hours.

The wonderful thing about Lela was that she was “Mom” to a bevy of young struggling starlets. She directed RKO’s Little Theater, where promising young people from other studios also came to be tutored by this wise, warm woman. When some young kid at Warner Bros. or MGM was hauled into the clink for drunken driving or some other charge, Mrs. Rogers was usually the first person the cops would telephone. “One of your kids is here,” they’d tell her, “asking for Mom Rogers.” And she’d drop everything and hurry to the police station.

Just before we started filming Roberta, Lela got a phone call from Pan Berman at the front office. “We’ve put four models under a short-term contract for Roberta,” he told her. “Three of them may be star material. Then there’s a kid named Lucille Ball. Don’t pay any attention to her. Berny Newman hired her, I don’t know why. She’s great at parties, a real funny kid, but I can’t see any future for her in movies.”

Lela thought otherwise. She told me years later, “I noticed the twinkle in your eyes, and the mobile face, which is a must for comedy. I also sensed a depth and a great capacity for love.”

“What would you give to be a star in two years?” Lela asked me when I first was getting to know her.

I gulped and answered, “Gee, what d’ya mean?”

“Would you give me every breath you draw for two years? Will you work seven days a week? Will you sacrifice all your social life?”

I had observed Ginger’s dedication on the set, and I knew that Lela meant every word. “I certainly will,” I promised.

“Okay,” she said, “let’s start.”

Lela was the first person to see me as a clown with glamour. She pulled my frizzy hair back off my brow and had a couple of my side teeth straightened. Then she sent me to a voice teacher, and told me to lower my high, squeaky voice by four tones.

Lela used to say, “A comedienne who does Ginger’s style of comedy has to be good-looking. You should be able to sit and watch her read the telephone book, and with either Lucille or Ginger, you can.”

Mrs. Rogers would arrive at her theater building on the RKO lot after lunch. Whoever wasn’t working on some movie set would join her then; the rest would arrive at six p.m., when shooting generally stopped. To break down our reserve, she put us in improvisations. At three in the morning we’d be begging, “Oh, please, Mom . . . just one more . . . let’s do just one more.” Then we’d be going home at four, punchy with weariness but feeling so wonderful!

To me, the live theater was it, and still is. Lela mounted us in good plays and rehearsed us steadily for four or five months. Then we’d perform the play nightly except Sundays for the same length of time. Her productions were an incredible showcase for young talent. Admission to the plays was twenty-five cents. People flocked to our theater from all over town and from as far as New York. Often, we had directors and producers in the audience, and critics too. I met Brock Pemberton and his wife backstage one evening. For months after that, he tried to find me a part on Broadway.

I soon became part of a small, intimate group centered around Ginger, who was about my age. On weekends we played tennis, went swimming, and double-dated at the Ambassador and the Biltmore. The group included Phyllis Fraser, Ginger’s first cousin, who is now Mrs. Bennett Cerf; Eddie Rubin; Florence Lake; and Anita “The Face” Colby. Ginger was dating Lee Bowman, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and Orson Welles; often I went along.

It was such a busy, happy time for me. Lela took the dungarees off us and put us into becoming dresses; she ripped off our hair bands and made us do our hair right. If we went to see a big producer in his office, she cautioned us to put on full makeup and look like somebody. She made us read good literature to improve our English and expand our understanding of character.

She drummed into us how to treat agents and the bosses upstairs. Lela believed that sex is more of a hindrance than a help to a would-be star. More actresses have made it to the top without obvious sex appeal than with it. Lela taught us to dedicate ourselves to our work and to ignore the nerve-racking rumors of calamity issuing from the front office. I never played politics at RKO, and it wouldn’t have helped if I had. RKO had eleven presidents in fourteen years. Lela advised us to work on ourselves and pay no attention to those corporate machinations.

Lela wouldn’t tolerate anyone taking advantage of her charges. One producer at RKO kept sending her his protégées to include in her classes. Lela kept throwing them out, until her patience was exhausted. One day another protégée arrived, saying coyly, “Mr. X sent me.”

Lela picked up a telephone and told that producer, “I am not Madam Rogers, and my workshop is not a whorehouse. This girl you sent me today has no talent whatsoever and no future in the theater. So put her where you had her last night and keep her there.” That was the last we saw of those gamy dames.

My first contract at RKO was for three months; this was extended to six months, and then to a year. On May 12, 1935, our “Cleo-baby” turned sixteen and was finally allowed to choose where she wanted to live. She immediately left her father in Buffalo and joined us in Hollywood. Cleo was so happy to have a mother again she wouldn’t let DeDe out of her sight.

I drove directly from the studio to the bus terminal to get her in my secondhand Studebaker Phaeton, my first car. Cleo was overwhelmed at the sight of a “real movie star” in full stage makeup, false lashes, big picture hat, and polka-dot silk dress. I was back to making seventy-five dollars a week and thought I had arrived.

My contract had been extended to a year, but as 1935 drew to an end, Lela found me in tears. “Last night at midnight was the last hour they could pick up my option,” I told her. “I guess I’m through.”

Lela stormed up to the front office and learned that indeed I had been dropped. A new president had been installed and was effecting “economies” by cutting down the payroll.

“Very well.” Lela shrugged. “If Lucille goes, I go. She’s the best student I’ve got. I’ll take her to some other studio and manage her like I do Ginger.”

The bosses paled at this threat, and I was immediately rehired. Lela told me that the legal department had made a mistake about the date of the option. “They may ask you to take the same salary, without a raise this year,” she added. “And if I were you, I’d take it.”

So there I was, safe for another year. Lela taught us never to see anyone as bigger or more important than ourselves, but she discouraged outbursts of petty temperament. It was very bad, she said, for a young player to get the reputation of being “difficult.” This was brought home to me one time when my hot temper got out of hand.

I was sitting before a makeup table one morning when the head makeup man, Mel Burns, rudely told me to get out; Katharine Hepburn was on her way down. She had been hired at $2,000 a week and was held in great awe and respect by everyone on the lot. So with one eyebrow and no lipstick on my face, I hurriedly gathered up my things and left. After Mel Burns star

ted working on Hepburn, however, I realized I had left my eyebrow pencil behind.

I came back drinking a cup of coffee and stuck my head through the little talking hole into the dressing room. Mel Burns ignored my polite request for the eyebrow pencil and went on applying makeup to Hepburn. I asked him again, and then a third time. He made some stale reply. I had been putting up with this guy for a long time and had had about enough. Suddenly the coffee cup left my hand and went sailing into the dressing room, narrowly missing Hepburn’s celebrated head.

A little later, Lela was summoned to the front office. “This Lucille Ball is temperamental—we’ll have to get rid of her,” Mr. Berman said.

“Of course she’s temperamental, or she wouldn’t be worth a cent to you or anybody else,” Lela flared up. “So is Mel Burns, so if you fire her, fire them both.”

I was in the doghouse all right, so to show everybody whose side she was on, Lela took me to the commissary for lunch. Hepburn walked over to our table and said soothingly, “It’s all right, Lucy.” Then she added, “You have to wait until you get a little bigger before you can practice temperament.”

Lela expected all of us to show up at play rehearsals, whether we were in the production or not. As Phil Silvers is fond of saying, “If you hang around show business long enough, you learn!” We all spent hours and hours in the darkened theater watching rehearsals.

We were putting on A Case of Rain, with Anita Colby in the lead, when Lela called me at ten o’clock one morning. “Anita’s sick and can’t go on tonight,” she announced. “Will you take her place?”

She then explained that there was no time for a full rehearsal. “My assistant will go through the lines and moves with you,” she said.

I had, of course, studied the play, and watched the rehearsals, but there’s a big difference between this kind of mental approach and the actual performance. I arrived at Lela’s theater about eleven a.m. and stayed there all day, until the opening at eight o’clock that night. I don’t know how I did it, but I played the lead without missing a line or a cue, and got twenty-five more laughs than usual.

Afterward Lela came to me and said, “Lucille, if you’re in the theater for fifty years, you’ll never face a more difficult task. You’ve been through the worst that can happen to a performer. I hope you’ll always rise to challenges like that.”

Only recently did I learn from Lela that my jumping in at the last moment was her way of testing me. Anita’s sudden “illness” was a put-up job.

Sitting in the back row of Lela’s Little Theater one night was Pandro Berman. He was short, dark, vital, and still in his early thirties, the boy wonder of the industry. He produced all the Astaire-Rogers musicals and had often been locked in mortal combat with Lela over Ginger’s lines or dances or her attention-getting costumes. One of Ginger’s bouffant ostrich-feather dance gowns almost suffocated skinny Fred. But Lela fought Pan Berman for every feather, and won.

As RKO’s top producer started to leave the theater after the performance, Lela came up to him and crowed, “That was Lucille Ball who played the lead tonight on only a few hours’ notice. She’s the girl you said had no acting potential.”

For once, Mr. Berman had no counterattack to the “mother rhinoceros.” “Yes, I know,” he told Lela quietly, and stole away.

Lela kept telling the RKO producers and directors, “I have a passel of good talent, and when you’re casting bit parts, I want you to use my students.” Director Mark Sandrich came to her one day when he was casting Top Hat, and Lela talked him into giving me a few lines. It was my first real speaking part, and during the filming I was so nervous and unstrung that I couldn’t get the words out. They phoned Lela and told her I wasn’t doing well and would have to be replaced. So Lela hied herself right over to the set.

My scene took place in a florist’s shop, where I was supposed to make some biting remarks to some man about Fred’s sending flowers to Ginger. I stumbled and blew my lines until Lela said to Mark Sandrich, “Reverse the lines. It’s not in character for the girl to make those biting remarks. . . . Give them to the man.” So we reversed the dialogue and everything worked out fine.

My next movie was Follow the Fleet, which was another big splashy Astaire-Rogers musical, with Betty Grable in one of her early parts. Ginger and Fred sang and danced to Irving Berlin’s “Let’s Face the Music and Dance,” “I’m Putting All My Eggs in One Basket,” “We Saw the Sea,” and “Let Yourself Go.” It was based on the stage comedy Shore Leave, with little plot but great songs and dancing. I played Ginger’s friend. The picture opened at Radio City Music Hall in February 1936, and shortly afterward I got my first fan letter, which I still have. It was addressed to the front office, and said, “You might give the tall, gum-chewing blonde more parts and see if she can’t make the grade—a good gamble.”

From Follow the Fleet, I went into the second lead of That Girl from Paris, with Lily Pons and Jack Oakie. On the set, I clowned continually. One day an older man came up to me and said, “Young lady, if you play your cards right, you can be one of the greatest comediennes in the business.” I just gave him a look. I figured he was one of those guys who came around measuring starlets for tights. Then I learned he was Edward Sedgwick, a famous comedy director who had coached Buster Keaton and Jack Haley. Eventually, Ed Sedgwick taught me many comedy techniques—the double take and the eye-rolling bit and how to handle props. He became Desi’s mentor, and his wonderful, witty wife, Ebba, my confidante. They were both as close as father and mother to us.

Russell Markert, Lela Rogers, Ed Sedgwick—these were but a few of the experienced theater people who generously gave me a boost. I have a theory about the assists we get in life. Only rarely can we repay those people who helped us, but we can pass that help along to others. That’s why, in 1958, I reactivated Lela’s theater workshop with two dozen talented kids trying to get started in show business. My accountants referred to it as “Lucy’s Folly,” but Marie Torre called it “the most practical workshop in television.” I found it a deeply satisfying experience. It was my way of thanking Lela.

Freddy, Cleo, DeDe, Daddy, and I were all still living in the little three-bedroom rented house at 1344 North Ogden Drive with two fox terriers and five white cats. In the same way that I collected animals, Daddy built up a large circle of ne’er-do-wells and underdogs.

He suffered a slight stroke at seventy-one, and afterward became garrulous and even more worried about the state of the world. My dates thought him eccentric and a “character,” especially when he read aloud to them from the Daily Worker while they waited for me.

There’s no doubt that Daddy’s experience with the law in Celoron disillusioned him deeply about democracy. He had worked hard all his life; then overnight everything was taken away from him, unjustly. During the Depression he saw many of his closest friends also lose their homes and life savings through circumstances beyond their control. The furniture factories in Jamestown closed, the craftsmen were thrown out of work, and after a few weeks or months, most of them were penniless and on relief. And these were master craftsmen: proud, able men.

Daddy would complain about the hard lot of the workingman, and before we knew it, his garage became the meeting place of radical left-wingers and crackpots. I never saw any of these people, being much too busy working, but DeDe often said that they were taking advantage of Daddy’s warm heart. He was the softest touch in the whole neighborhood.

He would go to the relief board and battle for a total stranger. He was a sincere humanitarian, but also sentimental and unrealistic. For instance, he soon discovered that the corner of Fairfax and Sunset Boulevard, just a block from our house, was a favorite gathering spot of Hollywood’s call girls. Daddy would hurry over to some lady of the evening and press a five-dollar bill into her hand, saying, “Take this and go back home. You don’t have to work tonight.”

“Sure, pop, thanks a lot,” the woman would say. She’d pocket the money, walk around the block, and be back

at the same stand five minutes later. Daddy gave away his money every week, until we finally had to stop giving him any.

If we contradicted or crossed him, he became highly emotional. It was easier to agree with him than to risk his having a second stroke. We couldn’t keep a maid because he’d immediately tell her she was overworked and underpaid. I got him a job in the carpentry department at RKO where master woodcraftsmen were scarce. He worked one Monday, from seven until eleven a.m. It took him exactly that long to walk the wood turners out on strike—and they were getting very good money. Until Daddy arrived, it had never entered their minds they were the least bit underpaid.

After his stroke, Daddy was confined a good deal to a rocking chair. There was a tall tree near our sidewalk which he said interfered with his view of the mountains. “That goddamn tree is in my way,” he complained repeatedly. “I’m going to cut it down.” I explained this would be against the law. “It’s not our tree,” I told him. “It belongs to the city.”

A few weeks later, he changed his tune. “Someday that tree will blow down in a storm, you’ll see.” Sure enough, during a mild sprinkle, the tree toppled over. Then we could see that the roots had been cut, the sod neatly turned back for the operation and then replaced. Worse than that, the tree fell right on top of my new secondhand Studebaker, which was parked at the curb. It cost me four hundred dollars to get it fixed.

I was going at such a pace at the studio and in Lela’s Little Theater around this time that I wore myself down to 100 pounds. My normal weight today is 130. While I was in the hospital on a fattening diet, Lela asked me if I wanted a bit part in a play by Bartlett Cormack, Hey Diddle Diddle, which was headed for Broadway. Lela developed not only actors and actresses, but playwrights too. It never hurts a movie actress to appear in a successful play back east, so I jumped at the chance.

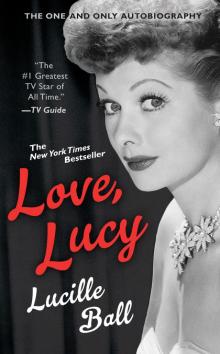

Love, Lucy

Love, Lucy